Today we received an email from a very disappointed customer:

“Hello

We bought two jars of honey from you guys in xxxxx market and we are not happy about its quality at all. It seems that you are feeding your bees with sugar as you can see unsaturated sugar in the side of the jar.

We are not happy.”

The email was accompanied by the photos on the right.

My first reaction was to get a bit upset because of course, our honey does not come from feeding our bees sugar syrup and of course, we do not adulterate it and of course, we would love each and every customer that purchases our honey to enjoy every single teaspoon of it.

And then I thought that this is not the first time that someone tells us they threw honey away because it went hard and they thought it was off. So maybe I needed to take this email as a good opportunity to put together some information to help clear up this common misconception and put this customer’s mind at ease.

So here we are…

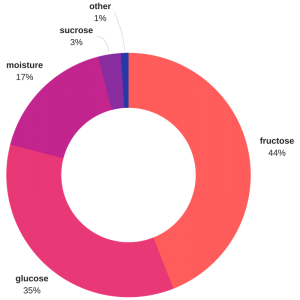

According to an AG Guide on Haversting and Extracted honey published by the NSW Department of Primary Industries this year, the average composition of Australian honeys produced from native and exotic floral species is as follows:

Fructose 44% Glucose 35%

Moisture 17% Sucrose 3%

Other less than 1%

Or if you prefer a pretty graphic…

In other words, Australian honey is made out of (in average) over 80% sugar, which is a lot of sugar in very little water, and that makes the solution unstable. And yet, this is the very reason why honey does not spoil as the water content is not high enough to start the fermentation process.

Glucose being less soluble than fructose is the crystallisation “starter” but other factors such as pollen or propolis in the honey (they act as a platform for the glucose crystals to start forming on them) as well as cooler temperatures can help speed up the process.

The higher the glucose to fructose ratio the faster the honey will crystallise. This ratio depends on the type of nectar the bees were feeding on, different flowers will produce a different ratio. Sometimes it happens in the combs themselves before the beekeeper even extracts it and some varieties take an extremely long time to crystallise.

Acacia flowers produce honey that doesn’t crystallise easily

Heated up/adulterated honey can look pretty on the shelf for a very long time, just the way consumers have been brainwashed to like things (pretty perfect lemons, straight-same-thickness carrots etc) but it doesn’t come without a cost.

Heat causes the destruction of enzymes and as well as loss of aroma and flavour. It also increases the content of the undesirable compound HMF (hydroxymethylfurfural). Fresh natural honey can have varying levels of HFM (usually below one mg per kg in the hive) but the levels soon start to rise with ambient temperatures above 20 degrees Celsius. The international food standards requires that the HMF content of honey after processing or blending shall not be more than 40mg per kg.

Canola flowers produce honey that crystallises very quickly

Well, for starters, plenty of people like the texture and the fact that it doesn’t drip everywhere when you put it on toast. If you are using in your tea or coffee, no problem, it will dissolve in the hot liquid. Same thing if you are using it for baking, or in marinades for your meat/fish.

But, if you still are not convinced and want to return your honey to its liquid form, do not despair, it is possible. Just put your jar in a bowl of warm water (around 40-degree Celsius) and let it sit there for a while. You might need to do this a couple of times but please, do not put it in the microwave, which of course is much faster, but will definitely destroy all the goodness of your honey.

The technical information for this article was mostly collected from:

AG Guide A practical Handbook. Honey harvesting and extracting. You can buy a copy here

Ana, thank you for writing this. It helping us here in Indonesia to have better explanation to our customer.

Sweet greeting from Bali Honey

We never keep our honey in the fridge and while we only purchase raw natural all is good with it for as long as it takes to eat

Excellent information. Thank you for educating those of us whom love honey, but know the minimum about it’s makeup. Respect!

I can’t wait until my honey crystallizes, I love to spoon it out and chew on it…!!!

Great article. Really helps explain the natural processes of good honey 🙂

Hi Ana,

Here’s a suggestion for customers who don’t like their honey crystallised.

I live in a chilly climate (Tasmania) and my honey always used to crystallise quite quickly. However, I’ve found a solution – I keep a large container of local honey on top of my hot water tank (nice and warm but never hot) and only decant a small quantity at a time from it for the kitchen.

Hi Ana and Sven

You would already know but your honey is delicious. We just opened a jar and had it with banana and pancakes

Beautiful

Keep up the great work